Online and in real life, there are always people that will never be happy with anything and try to drag everyone else down alongside themselves. These types of people will also tend to take out their anger on people who are different from the American ideal of a white cishet neurotypical able-bodied and conventionally attractive man with nothing “wrong” with him whatsoever.

But the truth is, the world is so much more diverse than just a bunch of carbon copies – but most types of media that try to accurately depict this diversity are criticized as “woke,” a term co-opted from African American Vernacular English (AAVE). The term originally referred to an awareness of racial prejudice, but in this context means believing that there are social injustices that need to be changed (and many use it as if it’s a bad thing).

But to many minority groups, representation is something extremely important, especially to younger people. According to an article published by Kevin Leo Yabut Nadal, PHD, in Psychology Today, for many minorities “a lack of media representation negatively impacts their self-esteem and overall views of their racial or cultural groups.”

Nadal speaks about his own experiences as a Filipino American, and his studies into the subject. Without proper representation, many people begin to internalize messages about themselves that tend to be very limiting: “scholars and community leaders have declared mottos like how it’s “hard to be what you can’t see,” asserting that people from marginalized groups do not pursue career or academic opportunities when they are not exposed to such possibilities.”

But Nadal also describes why media representation is important. Because of the limited social contact during the Quarantine, many LGBTQ youth developed intense mental health issues, and Nadal believes “amidst this global pandemic, visibility via social media can possibly save lives.” Positive representation can also reduce stereotypes, and aid in identity development for those growing up.

Much of the representation currently present does, however, tend to lean on unnecessary and unrepresentative stereotypes that harm identity formation and can harm self-esteem.

What does representation mean to current teenagers? While Nadal’s insights are important, with scientific studies to back up much of his information, the fight for representation remains, and many teenagers today did not grow up with positive representations.

For Valentino R. (he/they), a homeschooled student in 10th grade, he “didn’t really see people of [his] ethnicity or groups represented in the media, but when [he] did [they] felt they were portrayed in a negative light,” and when he did, “certain over generalizations that have been made over the years, [like] Mexicans/Latinos are often portrayed as being brutish or very hostile in certain ways.”

Asha Hart, Class of 2025 (he/him), adds that while he saw himself in media, those depictions tended to “magnify issues about me, which I believe becomes inaccurate as it accentuates my flaws instead of what I’m good at, thus diminishing others’ views of me when I tell them that I have such characteristics.”

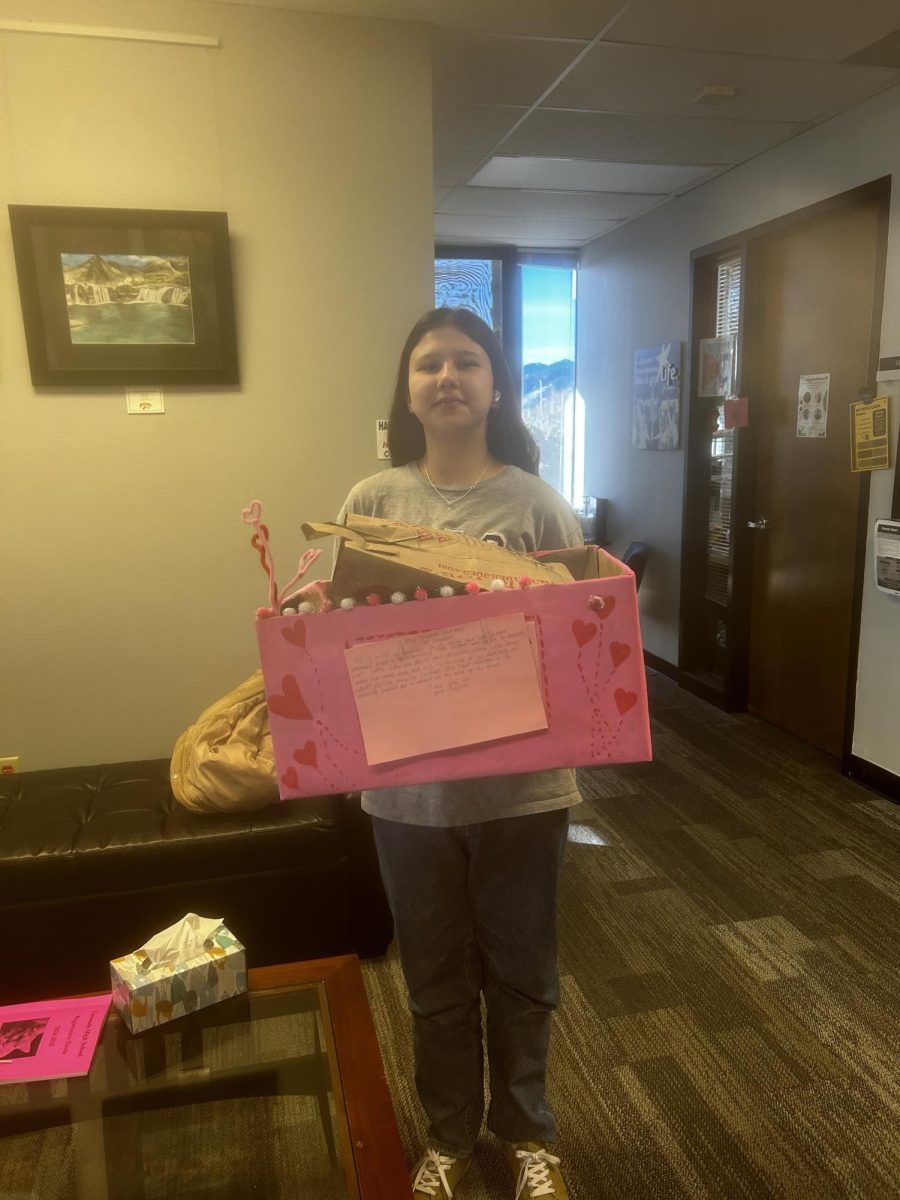

For me, personally, the representations of myself have always been rocky – I loved them because they were all I had to see myself in, but looking back, they were never that good. For example, I rarely saw Native American characters, besides Pocahontas in the Disney movie – which, in it of itself, is problematic. The idea of the “good native” compared to all the other “brutal natives” and so on. No one thought like me, and no one felt really “like” me.

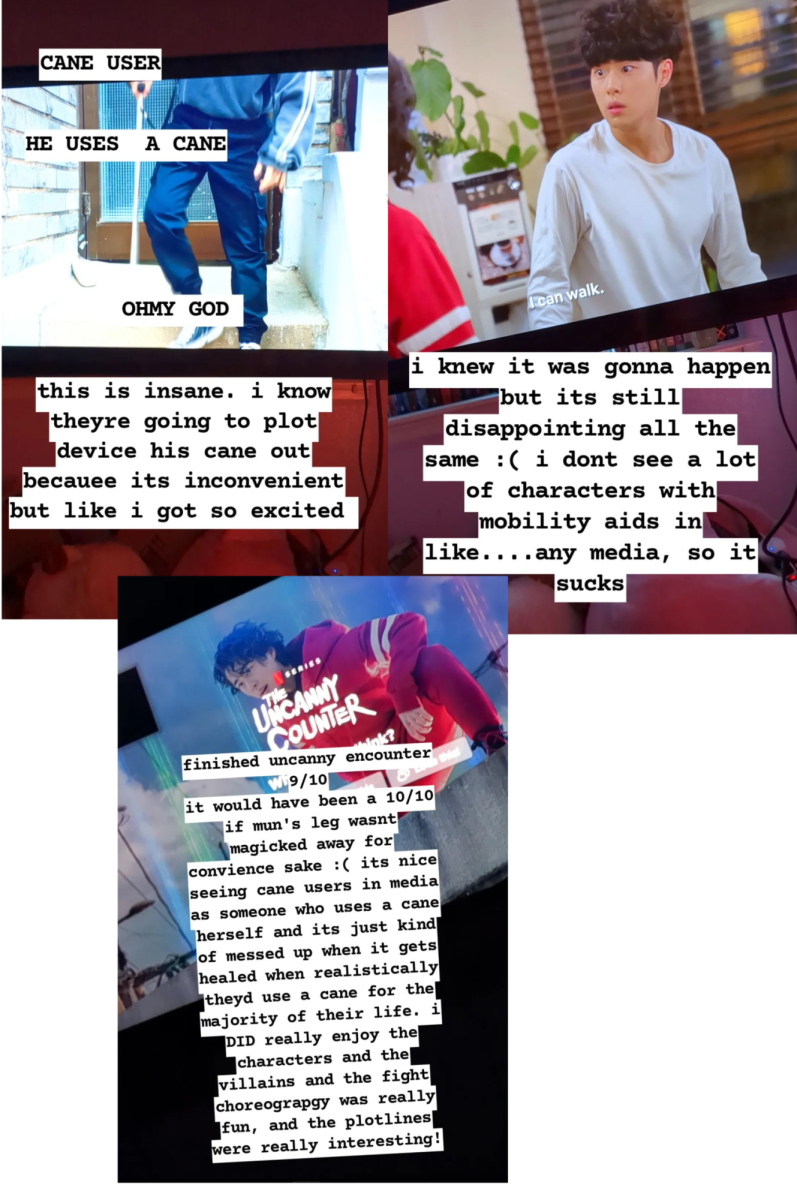

And seeing people that use mobility aids is even rarer. When mobility aids are introduced into stories it’s presented as a problem that can be magically healed. For example, So Mun in the Korean drama The Uncanny Counter, who uses a cane because of a childhood accident. But when he becomes a counter, his leg is magically healed, and he no longer needs it. This dilemma occurs more frequently than able-bodied media consumers are aware of; the disabled hero is no longer disabled because their disability proves to get in the way, or is irritating to draw, depict, or fit in the scene.

To Valentino, “HEALTHY representation in the media is very important because it de-stigmatizes people who are of certain minorities, such as people who are gay being portrayed as heroes or villains regardless of sexuality or race, painting a better image for these groups.”

Rowan Bullock, Class of 2024 (they/them), agrees on this point, going on to add that representation “can both give people in minority groups someone to relate to and see themselves in, and normalize otherwise foreign concepts to people not in those groups. As we try to work towards a more equal and accepting future, this is very important.”

Rowan also adds that, in their experience, “there are lots of characters I relate to in media, but not a lot of them are really ‘representation.’ And whenever there is actual representation of me, I’m usually too excited to care exactly how accurate or good it is. sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s not.” Relating to a character that is not explicitly “x” or “y” is a common occurrence, leading to people making “headcanons,” types of alternate canons/realities within a member of the audiences’ mind.

Valentino, Asha, and Rowan saw types of representation in many different pieces of media, including Steven Universe, Dog with a Blog, Adventure Time, The Never-ending Story, and She-Ra and the Princesses of Power.

The consensus between these three is that the media needs to change in some way – mainly revolving around the use of stereotypes in fiction to generalize groups.

Rowan calls for “less robots/aliens as the only representation for nonbinary, asexual, and autistic people. It seems like a good analogy at first glance, but it is very, well, alienating. As a nonbinary person who has a very female body, only seeing characters be nonbinary if they also do not have a biological sex is missing the point, in my opinion. The main thing to understand with the spectrum of gender identities is that sex does not equal gender. and sexless characters don’t really show that.”

Asha explains that “the media could use less falsities in how certain people present themselves. Things like filters and photoshop create an unrealistic beauty standard that is detrimental to people’s self-esteem.” Using a common problem on social media that creates unrealistic beauty standards for young girls and boys, leading to unhealthy dieting, self-harm, or other similar actions, Asha draws a stark comparison that highlights the damage it causes to viewers.

Another thing that needs to change is the way people treat existing representation. Spend any amount of time on any social media platform, and you’ll find all sorts of vile people. These people tend to seem like regular, nice people, but once minorities gain a shred of representation, they respond with hatred and vitriol.

The cause of this hatred may be white fragility – a concept that applies when white people vehemently deny the existence of prejudice and racial inequality. White people have lived with privilege since even before the creation of America, and the concept of that privilege being acknowledged or taken away in the slightest is enough to shake the hidden racist into revealing themselves.

An example is the general internet’s response to a fancast of Tangled including Avantika as Rapunzel rather than another blonde, white woman that is found everywhere in media. Many of these “good” people took to the internet, spewing racist remarks to Avantika. These posts gained hundreds of thousands of reposts and likes, all agreeing with the idea that Avantika could not fit the role, not because of her acting skills, but because she is Indian.

This response was even worse back in 2012, when Amandla Stenberg starred in The Hunger Games as Rue. The actress received death threats, a cascade of violently racist insults and remarks, and many revealed that they had no reading comprehension, missing that in the original novel she “[had] dark brown skin and eyes.”

Even in gaming fandoms, this sort of hatred of minorities is shared. In the majorly popular gacha games Genshin Impact and Honkai: Star Rail’s fandoms, lesbiphobia towards fans who claim characters are lesbians is common and cruel. Those who enjoy ships between two female characters must be careful if browsing for fan work, as corrective rape is a commonly hidden trope in some fanfictions to “trigger” them. Racism and orientalism go unchecked, and fans that speak up about these problems are accosted by racist remarks, insults, death threats, and even further.

Rowan theorizes this response stems from feeling threatened and uncomfortable, explaining that “they may not think of themselves as ableist/rascist/transphobic/homophobic, but seeing representation makes them acknowledge minorities, which can reveal prejudices they don’t know they have.”

Asha takes a similar perspective, positing “they respond this way due to these individuals being raised or eventually becoming so closed minded that they reject other opinions that are against their values.”

Valentino sums it up succinctly, adding that people “usually tend to react this way out of immaturity and racial bias.”

All three of them also add how they think this can be changed.

For Rowan, “they need to acknowledge these prejudices and work to the root of them. No one is free of bias and it’s no one’s fault that they grew up with certain beliefs, but it’s important to realize when you’re being a jerk and ask yourself why.”

Asha believes that “making efforts to be more open minded, even if it is awkward at first, is what I believe to be one of the only methods to overcoming this.”

Valentino gives their opinion, saying that “a healthy way to change and mend these behaviors would be to give these people positive experiences with the groups, along with teaching them that these behaviors are harmful and worth nearly as much effort as they require.”

Online spaces are the safest for minorities, and the consumption of mass media can create more positive representation. But many fear the need to expand beyond the white cis-heteronormative values – but this only exposes a need for self-reflection. It should not be such a problem that people want to see themselves, but unfortunately, without the needed self-reflection of the white cishet (etc.) masses and awareness of these issues, it remains an issue.

Without self-reflection, representation turns into an “us against them” conflict. But it’s important to realize that representation will not take away from others’ representation. In Rowan’s wise words, “more representation for minorities doesn’t mean less representation for the majority.”

Kevin Leo Yabut Nadal’s article: Why Representation Matters and Why It’s Still Not Enough